Archaeology and Uncovering the Mess

A Second Cohort of Archaeologists Play, Create, and Reflect with Artifacts

“I tell this story a lot,” Nika shared, “I was running one of these digs, and our community group had been hired as the contractor for a CRM (Cultural Resource Management) project. It was right next to a site where we’d been doing volunteer work, along a stream bank. Most of the crew were retirees, and one of them, easily 75 or 80 years old, showed up with his own breaker bar — a 12-pound iron rod you can use to bust up boulders. He’d brought it himself because he wanted to help.

We were digging along the stream bank, and at about three feet deep we hit the channel lag; the cobbles at the base of the channel. My co-director and I told him, “Hey, you don’t need to keep going. There’s nothing underneath that, you’re good.” But he said, “I’m gonna go a little bit longer.” So we told him okay and went off to record the shovel tests for the other volunteers.

When we came back an hour later, he had dug two more feet down through solid cobbles. And out of that, he pulled an archaic point and a jasper core.

This was two feet below where anyone’s methodology or guidance from the state would say to stop. Any field tech worth their weight in salt would have just stopped at that point. This guy decided to just keep going and he made this incredible find."

Terroir and Affordances

I care a lot about these kind of spaces, where we start with only a loose sense of direction and allow ourselves to pursue something uncertain from the outset. This is like the volunteer in the story, who kept going even when the outcome wasn’t guaranteed. Purposeless dialogue, or unstructured and aimless talk, generates some unexpected insight and intimacy between people. It’s not about saying and doing whatever comes to mind, but about following a thread whose end we don’t yet know; pursuing something.

Loose, collaborative experiences capture this grand mess of pursuing something. Everyone arrives suitcased and dressed in location, personal community, and recent baggage from the week. Their combined work is untidy and does not usually end in a perfect, sanitary sculpture, but still it arrives at a place of value and nuance. The mess has potential to be captured in a good light without expecting a solidified story arc.

I’m reminded of a cheesemonger who has described cheese making by its microbiology; where each specific place and people, including their imperfections, hold a different bacterial colony that affect the final pasteurized taste. This is cheese made from a natural routine and environment, instead of holistic intention of carving an environment to perfection:

“For me, terroir is rooted in a subjective bodily realization of a common aromatic profile existing across multiple milk foods made at one location, or in a small region. I also use it to refer to the layers that shape that unique [cheese] profile, such as cultural terroir (the tools, recipes, folk knowledge), or barnyard terroir (bedding materials, water troughs, building materials), which influence the more obvious botanical (pasture and animal feed) and microbial layers.”

— Trevor Warmedahl, Concentric circles of cheese terroir.

As an aside, he has a book coming out in February!

Within part one of this archaeology series, we discussed how affordances — the potential actions an object or environment offers to an actor — can be reflected both in archaeological methodology, but also in the tabletop game genre where we can see how players engage with tools and prompts provided in order to place aspects of themselves into fiction. Our environment offers us a stage to play in, and we don’t always have perfect control over what that ends up making.

So, with all these thoughts strung into the air semi-aimlessly, I hope you enjoy another mess of stories based in specific, individual experiences. Today we’ll be continuing our discussion with a couple of new professional archaeologists, exploring their careers while using the worldbuilding game To Care is to Cairn (TCITC) to help lightly guide the conversation.

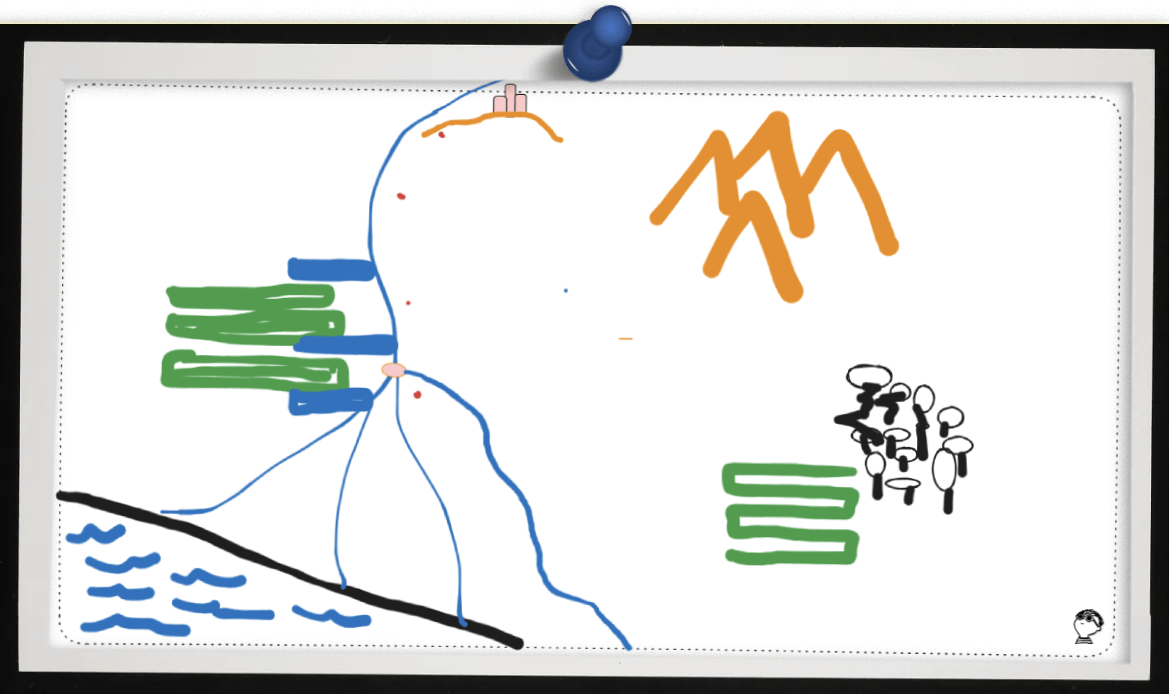

Participants started by collaboratively constructing the game map by improvising landscape features. Jay VanderVeen, a long-time four-field anthropologist and professor, ‘Bob-Rossed’ in some trees and described the eastern forests. I helped guide and affirmed contributions, extending the map with rivers and a delta. Finally, Nika Zeitlin, a CRM field archaeologist, created a coastline for the river to drain into.

From there, Jay and Nika collaboratively developed an early agricultural settlement on the game map. Jay proposed a pre-civilization, post-hunter-gatherer setting with emerging agricultural practices, while Nika expanded on the concept with the introduction of early Bronze Age technology and metalworking sites. They designated spatial relationships between fields, irrigation, and specialized satellite locations, while considering the placement of household gardens and pottery kilns relative to villages and metalworking areas. They would often differ to each other’s expertise.

We had a third member, Ryan, that was initially going to join our session. However, he experienced an actual archaeological emergency that night. It required driving off as “a once-in-a-life-time find was made at 4pm and we had to scramble lights and dig until 9pm central to safely rescue it. It was a couple of 2,000 year old Native American pots found intact in a fire-pit which can be radiocarbon dated and tested for foods ... I have only seen these 3 times in my 35 years of digging and this is only the 3rd of this kind of pot found in my Midwest USA region.” This is definitely one of the more reasonable explanations someone has given me to miss a game night.

War and LARPing

“I’ve kind of done everything,” Nika started during some introductions, “I like to say I’ve put a shovel test into 30 of the 50 states. I shovel-bummed for quite a while. I went to grad school at UMass Boston, where I did my master’s degree on Viking Age iron smelting in Iceland. So my research was in historical archaeology, but my jobs and fieldwork were mostly on colonial sites in New England. During the summers, though, I spent three summers in Iceland doing my own research and working with my advisors. I’ve also worked a lot on community archaeology projects, training volunteers in archaeological methods. I’ve taught for field schools as an instructor, and I really find a passion in teaching skills, methods, and theory through a hands-on approach.

A lot of my work has been on military sites in Pennsylvania—specifically, prisoner of war camps from the Revolutionary War. My very first dig in the UK was a POW camp on the Isle of Man, where I worked on internment sites of German ethnic peoples imprisoned during World War I and II. And then in Pennsylvania, it was British prisoners from the Revolutionary War, from the Battle of Saratoga. In both places, I engaged a lot with local communities, many of whom had ancestors who were guards. So it was a very different public angle—more about the descendants of the guards than of the prisoners. A lot of what I do is trying to find a balance of interpretation between both sides.

Before I was an archaeologist, I worked for a LARP (Live Action Role Play) company. I started as a camper, then moved on to counselor, staff member, and eventually director. The program worked a lot with kids, especially kids with special needs. A big part was working with kids with autism who struggled with social cues. Dropping them into a LARP environment, handing them a handbook, and saying, “Here are the rules for society,” really helped them learn. My undergrad was in psychology, so I brought a lot of theory of role-playing into LARPing. A lot of the basics of role-playing games come from psychology—processing things as another character. Bringing that into gaming is really important to me, helping people have emotional experiences.”

This was around when Nika shared the volunteer digging story from the start of the article, where the older gentleman found an archaic point and a jasper core.

“Because of him, we ended up putting the site into the survey, going through the full process.

I remember later going to a job where the PI—the principal investigator—was the guy we had underbid for that project. And he was mad at me. He said, ‘You jerk, why did you take that project away from us?‘ And I told him, ‘Because we found a site.’ He said, ‘We wouldn’t have found that site.‘ And I said, ‘That’s exactly why we won!’

So… that rambling story is just to say I’ve seen a lot of passion come out of people getting to be archaeologists. And I think there’s a fine line between showing people the fun and satisfaction of the work, and also breaking their hearts with the realities of the industry and career.

When I work with younger people, I think field school is, more than anything, LARPing as an archaeologist. Everyone shows up with their Indiana Jones hat on their first dig, full of excitement. Teaching in that environment means finding ways to channel that energy, while also laying out some of the harder truths.

On the flip side, being a LARPer—playing as an adventurer, a warrior, all these different roles over the years—was one of the things that led me to archaeology. I wasn’t interested in a desk job or sitting at a computer. I wanted to be outside, moving around, working with my hands. That came out of a love of being another character, being an adventurer. Also, I mean… my love of Gimli from Lord of the Rings, and the fact that I like to dig in the dirt. Who knows?”

Rituals and Play

The participants collaboratively developed the town’s mythological framework. Nika introduced a central legend of a hero who tamed the river and created irrigation channels, establishing agriculture. I clarified the hero’s absence from the present town, situating the narrative in time. Jay contributed a subplot linking a solar eclipse to communal responses, illustrating how myth integrates with daily life and identity in the game world.

Jay was constructing a polymetallic acorn object reflecting a solar event and was delighted at the creative freedoms a game could allow for. He was able to be an archaeologist but also finally see behind the curtain at the truth of our fictional society:

“We never get to find the reason why. It's always ritual purposes.”

Ritualization is not a simple act, but the contexts of acts. Rituals serve to fulfill various purposes, including reinforcing social bonds, expressing spiritual beliefs, or communicating shared cultural ideas through symbolic, repetitive, and communal performances. It’s simply deliberate action. Archaeology is the study of how people live, and we rarely get to truly know their deliberations; their reasonings, leaving ritualization to be a catch-all for anything not yet understood.

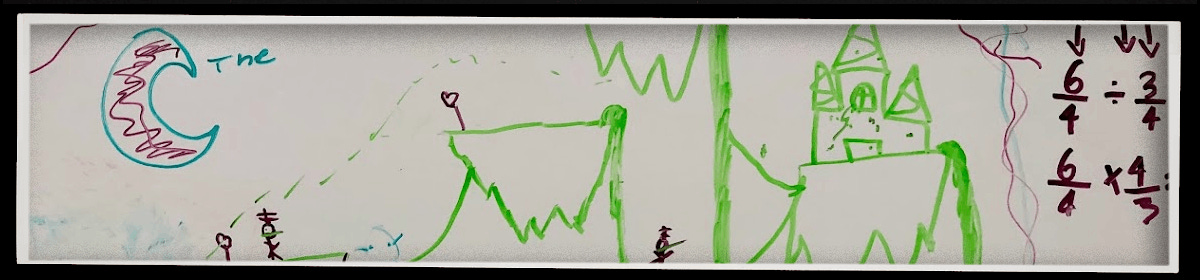

In-Game Prompt: “A child needs art supplies for a mural project. How do they procure the supplies? Who is the art for?”

Jay responded, “So the child is gonna make a totem for good luck for pregnancy for their older sister. They’re gonna use one of the net weights. It’s now loose from the reeds, and so it’s just hanging out on the shore. The weight got washed down and the child picked up a net weight. They’re using that with the ash, and drawing this totem.

The child doesn’t know the symbolic meaning of the net as a whole. The child only found the net sinker, which is a really cool-looking rock, and children love really cool rocks.”

Later when prompted about inspiration for this scene, Jay elaborated, “Kids are always picking things up, always testing things out, always doing the first try. So, if you pick up a piece of pottery and think, ‘Oh, this is very poorly made,’ maybe it’s not. Maybe it was practice. Maybe it was a really good kid’s version, because they were just learning.

So, we’re watching kids pick up something that once held a lot of community meaning and say, ‘No, it’s just kind of a cool rock, and I’m gonna use it for this. I’m gonna use it for art. I’m gonna use it for something that’s not gonna leave a lasting impression.’

I sort of think about this children question often, because when I was in school, all of my professors were saying, ‘The new ritual object?’, [as in, the new generalized answer for unexplained finds], ‘It was probably a kid.’ ”

Most popular portrayals of rituals and religions in media for instance overlook this role of the imperfect individual, be it a child or an adult. People don’t always act exactly to the societal average. For instance, a religious text is not the religion itself, because daily, lived practice rarely mirrors the written, formal proceedings of religious leaders. Instead, most people adapt practices in small ways, shaping them to better express themselves in the world and to connect with something greater. These improvised, unofficial routines are often more common than strict adherence to scripture.

Ritualization is a process. We can recognize the broad, generalized beliefs of a community - much like glimpsing a Catholic church sermon - but it is far harder to trace the personal meaning behind an individual’s object or act, such as a broken spear tip or someone’s saint medallion kept in their wallet.

Nika additionally explained that some sites are difficult to identify as ritualistically significant or not. Some Icelandic caves were once thought to be ritual temples, but later research revealed them as bandit camps containing stolen goods. There will always be strong debates between ritual and functional interpretations of archaeological sites.

Environmental Uncertainty

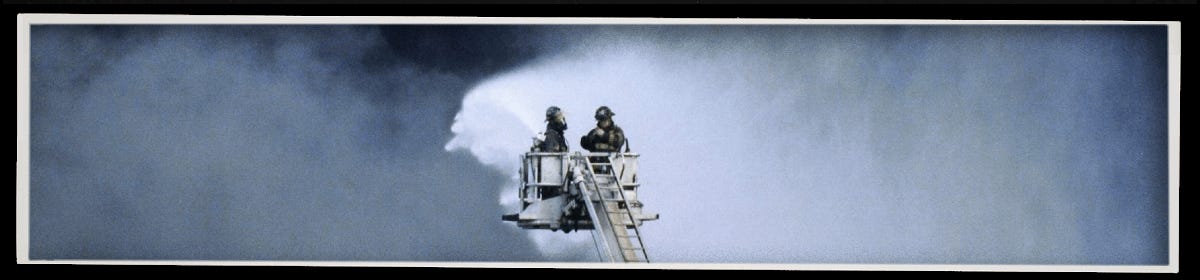

In-fiction, a massive Leviathan swam far upstream where its species had never before been found. It thrashed through irrigation ditches, slowed the water, then stranded and died near the town. Its rotting body became a catastrophe — fouling water, drawing pests, and threatening the community’s survival.

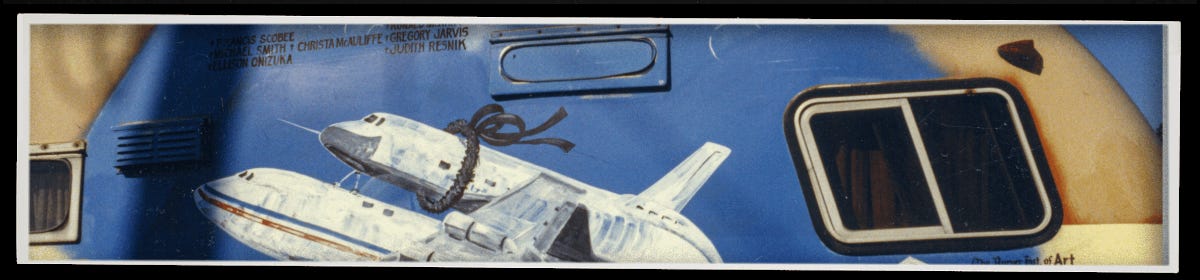

The townspeople forged a massive bronze culvert and drove it through the carcass, allowing water to flow again until the remains could be dealt with. This practical solution prompted further investments into netting fish and left lasting evidence in the landscape. Generations later after the creature rotted away the memory shifted. A myth taught how people had banded together to destroy the Leviathan in a grand, explosive act.1

The culvert stood as a quiet trace of the real story, while legend told of a heroic triumph.

Nika shared, “A lot of my research and experience has been through spatial settlement survey work. And so, the idea of making a landscape of sites was something that I was going to find fun. Thinking about sites in terms of specialized craft and specialization locations is something that I find really fascinating, so that's why I put the bronze making scattered around [in our game].

I put the coastline in, and was happy that you put in the stream, because that really feeds into a lot of what I'm encountering around climate change these days. Having a landscape evolve, especially near an ocean or a river, I just feel is a very realistic way of showing how a culture changes over time. I thought that was going to be a very classic way to explore how this game works with realistic factors.”

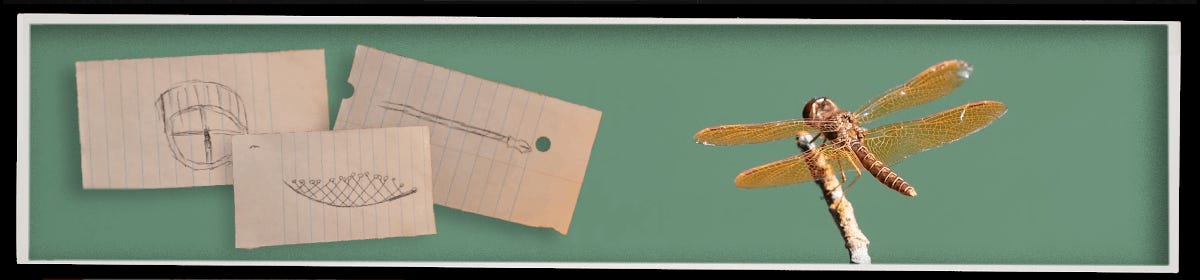

“In terms of the artifacts I made… I wanted something that was both ritual and functional, that's why I made the net. I find net sinkers all the time, and they're just… they're an artifact that we have tons of in our collections. Whether they're ritual or just functional is completely up to interpretation.

Both the net and the spear have a metallic or stone component, and then there's also an organic component that will disappear over time. So again, I wanted to see how these artifacts are gonna change as generations go by, and things degrade away.

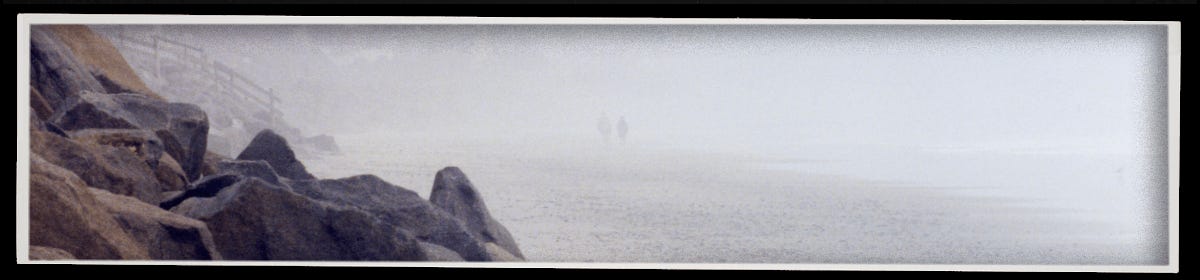

I've worked on a lot of coastal archaeology sites that are disappearing because of climate change. A riverside or a coastal Native American village is slowly getting eroded away by storms and waves, and so you're losing history that way.

In the work that I've done with FEMA, historic preservation falls directly in opposition to developing resilience plans. You have a historic village in New England where all of the houses along the coast are these historic buildings from the 1800s, but those buildings aren't going to survive a storm, and the only way to reinforce, then, is to destroy their historic integrity. Finding that balance between preservation and historic integrity is becoming a big conversation.”

Jay added in, “and same in the Caribbean, where we can watch the loss of sites. So not only are they getting destroyed on land, as the water is subsuming that shore, those sites are then gone from the land, but not necessarily entirely gone.

If there is some underwater archaeology, they can be preserved. And in fact, they might be better preserved underwater than in some cases when they were on land and then turned into a golf course or something else.

The additive function of these storms is how they bring all of that soil up, or the beach sand up, and they're covering former sites. We get a lot of hurricanes in the DR. The trees falling over are bringing up sites, but then the sand is covering the sites over again, and so on and so on…”

Nika described Iceland as a significant case study in ecological colonization. Before Viking settlement, the island had been entirely forested, but within approximately 80 years the settlers had completely deforested it. Following this transformation, wood became so scarce that driftwood carried from Siberia across the polar ice cap served as the primary timber resource. This legacy persisted linguistically in the name of Keflavík, meaning “Driftwood Bay.” Nika’s research examined how the Vikings adapted to this ecological change by shifting from wood as a fuel source for smelting to alternatives such as peat bogs and bones.

Further reading: Melting Sea Ice May Mean the End of Driftwood in Iceland

Here’s the thing I’ve come to firmly believe about worldbuilding. To be good at it, you’ve got to be a real sicko. What does that mean? Well, you can’t just be a tourist in your world. You need to live there. You need to pull back, into your mind, and exist there. You need to wake up there, eat there, go to work there, meet friends, make enemies, hate the place, love it, take vacations from it, change homes, change people, and in the end… always come crawling back.

— Mindstorm, Sicko Worldbuilding

In their article, Mindstorm noted that to worldbuild well, you can’t just be a tourist who marvels at the exciting new parts of a world. You have to be a “sicko” who has lived there long enough for the shine and polish to wear off, where even places of fantastic nature feel almost mundane, wrapped in the rusted shell of lived experience.

This isn’t to say everything must be cynical. Rather, bringing real-world exhaustion into fiction can create nuance and validation. Our participants, while active in their communities and deeply invested in caring for the environment and history, don’t always get to be the “adventurer or warrior.” As Nika put it, they are often intently working around “the realities of the industry and career.”

Through a connection to the Philly tabletop community, I met up with Ted; these stories reminded me of him. Ted didn’t quite get the chance to join our session, but I enjoyed grabbing coffee (as our excitement had us constantly talking over each other) to learn more about his experience as an archaeologist. While his personal experience with construction workers often circled around ‘dogmatic’ conspiracy, his headache this week would be truly hard for me to to witness.

Imagine discovering a stone structure over a hundred years old, with a complex and poorly-recorded internal architecture (a coal wharf from the late nineteenth century). Now, imagine the only way you can learn anything about it . . . is to watch an enormous drill rig blow right through it.

Without proper regulations in the United States to enforce any alternative, in part because history is so pervasive many believe it’s all-together too difficult to protect everything, Ted could do little more than watch the events unfold. At times he managed to pause the drilling long enough to take a few recordings, but after his third violation for disrupting the pacing of the project, all further information had to come from the drill itself: “the stratigraphic profile it revealed and the fragments of the coal wharf structure brought up in its bore”. Any deeper inquiries would have required driving new holes into the ground, and once again straight through the historic artifact.

In the end, we all keep crawling back to do imperfect-good under the constraints we’re left with.

Solar Eclipses

During a solar eclipse, the townspeople clashed metal tools and beat ceramic pots, hoping the noise would drive away the squirrel they believed was devouring the sun. It worked, and that was later integrated into other societal practices.

Back when Indiana was in the totality of the last eclipse, Jay had “went around and talked at adult daycare centers, schools, and retirement homes about the mythology that different people around the world had about the eclipse.” He expressed these insights well into the game as it progressed.

His dissertation research site was near La Isabela on the north coast of Hispaniola (an island between Cuba and Puerto Rico). This location was historically significant as the starting point of the Columbian Exchange. While Columbus’s chronicles had been widely studied, the perspectives and experiences of the Taíno, the indigenous people encountered there, had historically been overlooked.

When asked about common misunderstandings modern people have about historic beliefs pertaining to eclipses, Jay commented on how “Columbus may or may not have actually done anything with his knowledge of an eclipse … [There was the moment where] everybody was grabbing onto his boat, and then he said, ‘oh, I know an eclipse is coming, I'm gonna tell them about it and scare them off’, and so on. He wrote down that’s what they did, and how it was successful, and it scared everybody. But, the archaeologists are saying, these people have been living through eclipses for a long time, dude. They may have also had the ability to know what was going on. Even if they didn’t, the totality itself only lasted a couple of minutes, and the whole thing lasted, you know, just less than a couple of hours. So, they wouldn't be that freaked out, because even if they didn't cooperate, the end result was that the sun came back.”

I responded: “So, you’d need at most three minutes to get your way before things go back to normal?”

“Bingo, yeah.”

As an aside, Jay’s research examined dietary changes after Spanish-Taino contact. He noted, “in the Chronicles by Columbus he wrote that ‘the Spanish were starving’. And after traveling to the DR and looking around and saying, that's bullshit, man, there is plenty of food here, I asked why? The Taino had been living here for a long time. The Spanish had been starving not physically, but emotionally; psychologically.” The food simply didn’t feel fulfilling to them. “As long as people have been sailing away, they keep getting hungry for their mom's home cooking.”2

Reflections

The culverts may be gone, but the environmental impact they left behind is still evident. Ornate hunting spears found near the site were misidentified as ritual objects for coming-of-age rather than as practical tools. Even acorns, which had a role in daily life, became misinterpreted as a universal religious practice of the region.

At the close of our session, once stratigraphy had traced the final paths of the artifacts, participants completed an Exit Poll to share final reflections.

Nika considered “the mix of artifacts (spears and nut vessels) and the features (culvert, whale and irrigation channels) we created to be a great example of how artifacts and features both contribute to the archaeological record. The game demonstrates the relationship between objects and people, both ritual and utility. The game also demonstrated some basic principles of theorizing and interpreting and creating a narrative about an object or peoples … I included a lot of spatial diversity based on my research in settlement patterns. I also included metalworking into our world based on my thesis research.”

“Curiosity resulting from the immersive aspects of a game led to several questions being asked during and after the game sessions. During the game, questions relevant to apparel and equipment were more prominent, indicating a desire to understand the practical usage of everyday objects.” — The Intersection of Play and History: Integrating Historical Content in Tabletop Role-Playing Games for Education

Nika then reflected on some blind spots from our session: “When analyzing material culture in a professional setting, you are more likely to be using reference documents or collections to compare to finds in the field. Additionally, much of the interpreting we do is aimed at much more basic questions such as age or use since even those questions can require a tremendous amount of work. I don't think there were any challenges or biases that were encountered here because in the game you are creating the interpretation, which becomes a truth of the story in the game (to be modified as the rules suggest). In the professional world, biases and challenges arise in interpretation when materials are discovered to be misinterpreted in later research … I would add mechanics that encourage players to share artifacts through their lives. I would also suggest making some structure around the interpretation portion of the game at the end.”

Building on this, Jay added in his poll response: “I would have liked to see an epilogue, where people of the present or future look at the items produced and decide what to keep, display, or destroy.” While the game does follow up on where objects end up, he noted that considering how they are further used or displayed in modern society could be a valuable addition.

Nika continued, “One thing I noticed was that we ended up making a mono-culture in our world. Much of archaeology is about documenting how things change over time, and a lot of change comes from interacting with other cultures, whether that is through trade, exploration or, more realistically, colonialism. I think that while the focus of the game is about artifacts, it is important to remember that the objects help us understand people, not vice versa. In Native American archaeology we study pottery and projectile points primarily, but we have a phrase that ‘pots are not people,’ and while the artifacts tell us a lot about a cultural group, it is not the only thing in their lives, just the thing that survived.”

Together, these reflections emphasize how personal experiences drove how the game unfolded, for the good and for the bad. “Both game players put a lot of their own background into the game,” Jay remarked, “It was a perfect construction for those who know archaeology. Without the background, I would like to see what others do.”

“Findings reveal a clear predominance of games focused on the valorization of tangible heritage and historical content, while the processes of archaeological investigation are often oversimplified or marginal … Widely adopted engagement strategies, such as linear storytelling and collectible-based exploration, are rarely paired with more interpretive or methodological depth.” — Rediscovering the Past: Serious Games for Archaeology"

The Mess

As another aside, this month I have just started a new teaching job and met another new interesting person named Kyle. Over drinks, I realized the rest of us in the group were going on and on about sci-fi, which wasn’t really his specialty. So I asked what he was nerdy about. His answer: orchestral music. Specifically, Kyle lit up talking about the leitmotif, a recurring musical phrase tied to a character, idea, or moment. He described how a leitmotif can be reshaped, layered, and intertwined with other themes to really add power to the inner workings of a story. Even within his work with churches, he weaves in touches of fantasy-inspired leitmotifs, blending his passions into something meaningful for both himself and the community. This is one way Kyle adds to a great ongoing artistic conversation though his music.

With that story in mind, I want to return to that original idea of terroir. Whether it’s found in the mediums of cheeses, orchestral music, or archaeological tabletop games, terroir remains as an artisanal profile shaped by the personal and unique nuances of a particular place, time, and people. The food we eat, the shifting conditions of our climate, the games children play, and the religions we practice, and more all shape our collective terroir. This blend of experiences should not be taken as representative of everyone’s life, but it offers a meaningful way to bring together the memories of a few individuals and share interesting aspects of their world.

So, make a mess and add to the grand conversation.

Care to Cairn.

Part Three:

Credits

Participant information (such as name and position) was included in a fashion specifically requested by the individual. Participants additionally were provided an early draft version of the article to help correct for accuracy.

Unless otherwise noted, all images in this article were either maps and artifact cards from the game, photos taken by Kai Medina, or scans from originals photographs by his grandfather, Pierre Giroud.

Part One:

This was his explosive reference: Why did Oregon blow up a whale on the coast 54 years ago? Remembering exploding whale day